On this 261st Day of Genocide in Gaza, I admit to being stunned that the carnage has not only not ceased, but has become increasingly depraved. I won’t go into details as the words and images are easily found due to IOF soldiers proudly documenting their depravity/lack of humanity on social media sites. To counteract the sadism, I decided to offer a poem by a Palestinian, and so went in search of something that resonated.

I landed on a poem by Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008) who is “feted as Palestine’s national poet for his words expressing the longing of Palestinians deprived of their homeland, which was taken by Zionist militias to make way for present-day Israel. His poetry gave voice to the pain of Palestinians living as refugees and those under Israeli occupation for nearly a century.” And because this morning I began reading the Pulitzer Prize-winning Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy by Heather Ann Thompson, the Darwish poem I chose is “The Prison Cell.” Because just as the United States incarcerates more people than any country on earth (currently about 2 million people), Israel incarcerates thousands upon thousands of Palestinians and holds them without filing charges. It’s all connected. We’re all connected. And just as the incarcerated in the U.S. are treated as less-than and subjected to brutal conditions, so are the Palestinians. It doesn’t matter who we are or where we live on this planet: It’s all connected. We’re all connected.

In this spirit, I offer:

The Prison Cell

by Mahmoud Darwish

(Translated by Ben Bennani)

It is possible . . .

It is possible at least sometimes . . .

It is possible especially now

To ride a horse

Inside a prison cell

And run away . . .

It is possible for prison walls

To disappear,

For the cell to become a distant land

Without frontiers:

What did you do with the walls?

I gave them back to the rocks.

And what did you do with the ceiling?

I turned it into a saddle.

And your chain?

I turned it into a pencil.

The prison guard got angry.

He put an end to the dialogue.

He said he didn’t care for poetry,

And bolted the door of my cell.

He came back to see me

In the morning.

He shouted at me:

Where did all this water come from?

I brought it from the Nile.

And the trees?

From the orchards of Damascus.

And the music?

From my heartbeat.

The prison guard got mad.

He put an end to my dialogue.

He said he didn’t like my poetry,

And bolted the door of my cell.

But he returned in the evening:

Where did this moon come from?

From the nights of Baghdad.

And the wine?

From the vineyards of Algiers.

And this freedom?

From the chain you tied me with last night.

The prison guard grew so sad . . .

He begged me to give him back

His freedom.

—-

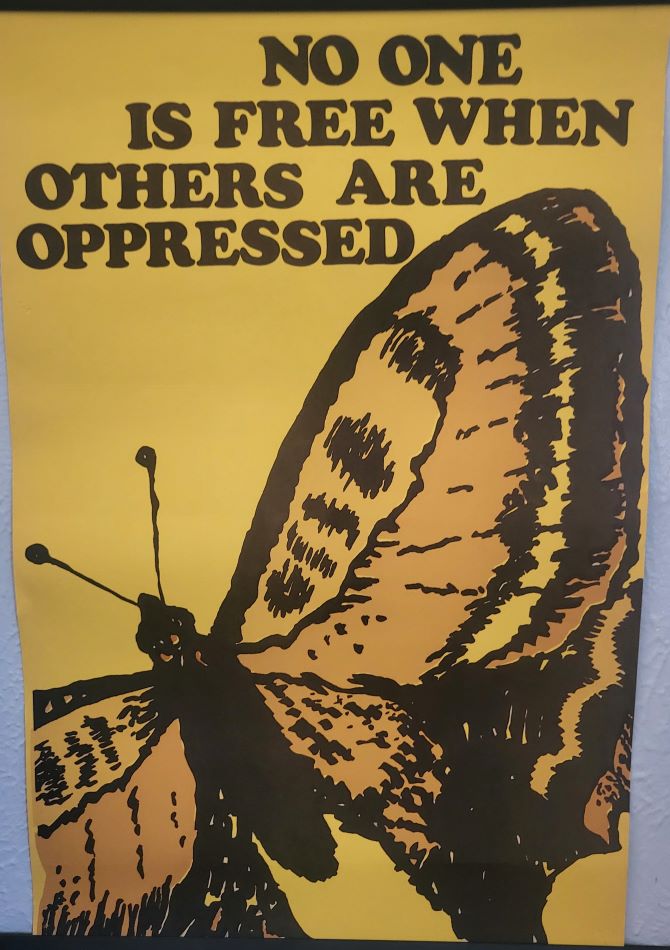

One final connection between Palestinians, the men in Attica in 1971, and me: this poster I unearthed in my basement yesterday, one I’d bought years ago (and possibly hung in my California classroom):

It’s all connected. We’re all connected.